Quamash EcoResearch

Ecological research in support of restoration and conservation

How do plant-pollinator communities respond to prescribed fire?

Restoration efforts often focus on preparing degraded sites with tools such as prescribed fire, then replanting native plant species. There are often two implicit assumptions: (1) other interacting species, such as pollinators, will show up automatically when native plant diversity is restored; and (2) restored communities will be more resilient to future stressors. We tested these assumptions by studying a series of prairies that varied in their frequency of prescribed burning and replanting, documenting interactions between plants and pollinators in these sites for 4 years.

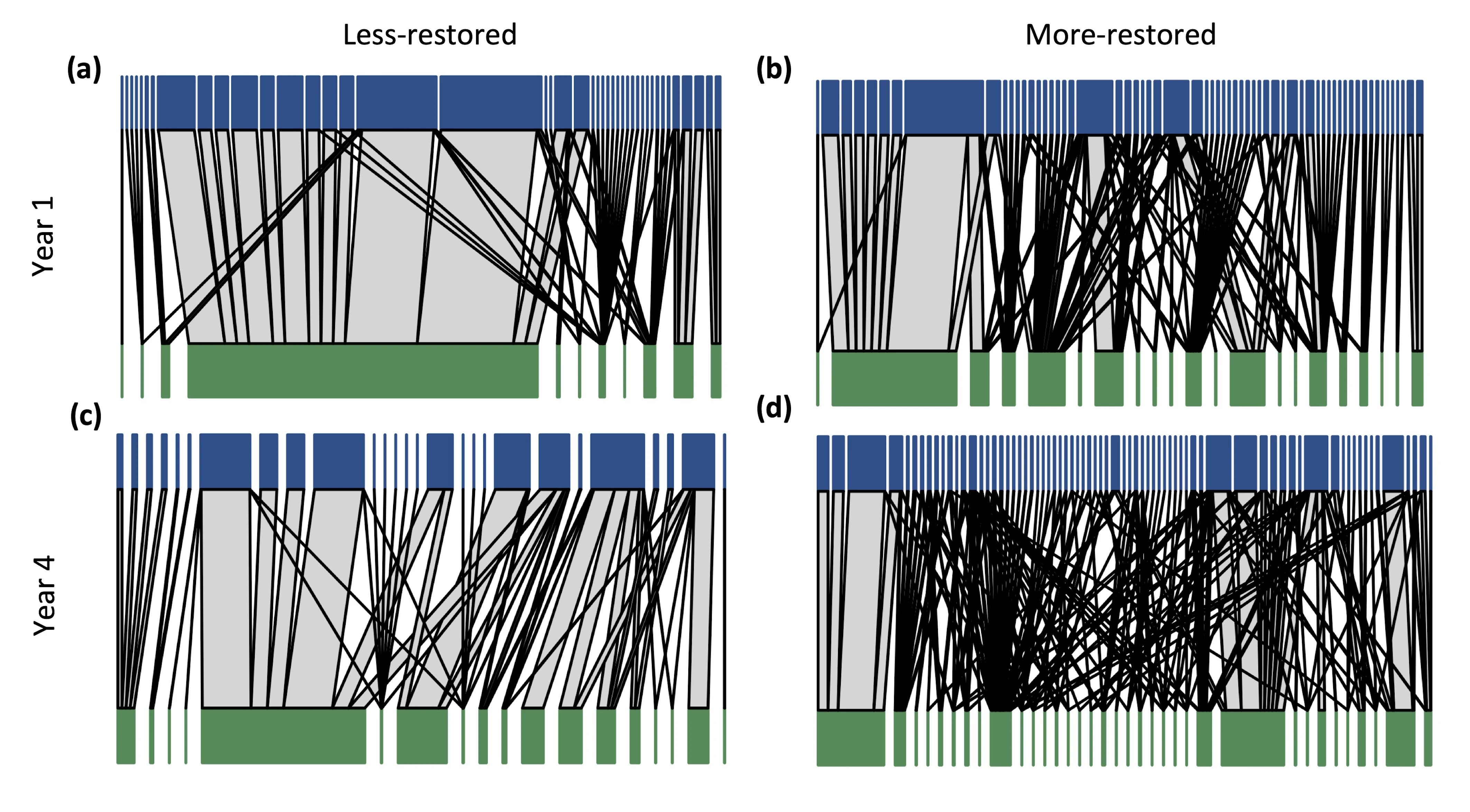

We used these data to construct plant-pollinator interaction networks (Fig. 1 below). We then tested the vulnerablity of these networks to losing a plant species. We did this by simulating the loss of the species and following the predicted cascade of secondary losses of other plants and pollinators (in response to the initial species loss).

Fig. 1. A less-restored site (no prescribed fire history; left) and a more-restored site (multiple repeated prescribed fires, right) in the first year of the study (top) and the fourth year of the study (bottom). The network images depict plant-pollinator communities (green boxes are plant species, blue boxes are pollinator species). Lines connect plant and pollinator if the polliantor was observed visiting the plant's flower (putative pollinator).

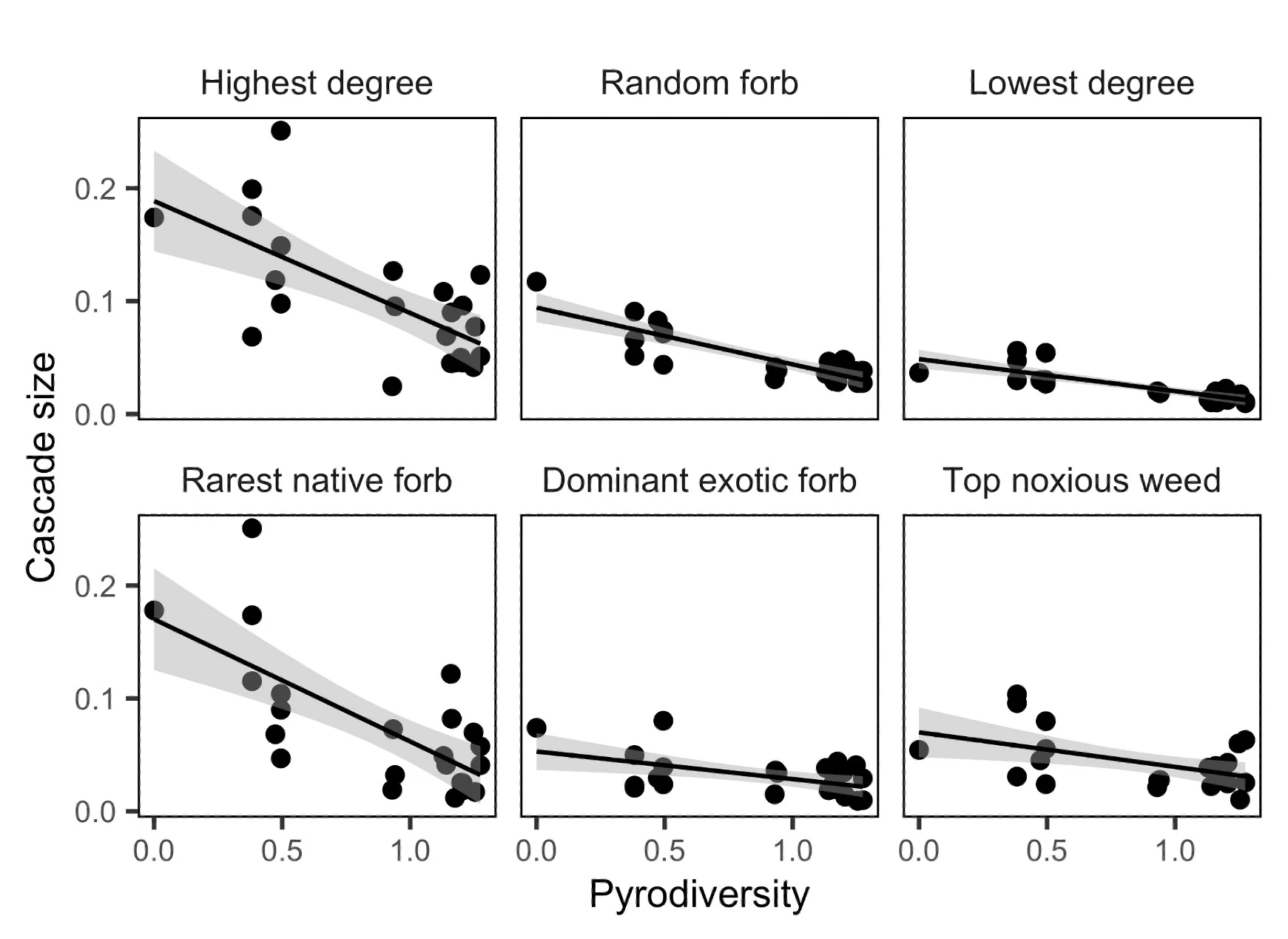

We used these data to construct plant-pollinator interaction networks (Fig. 1 below). We then tested the vulnerablity of these networks to losing a plant species. We did this by simulating the loss of the species and following the predicted cascade of secondary losses of other plants and pollinators (in response to the initial species loss).In examining the effects of losing a species, we tested six scenarios: three control scenarios in which we removed a plant species based purely on its position within the network, and three experimental scenarios in which we removed a plant based on its native or invasive status. In all scenarios, the deeper the history of prescribed fire (pyrodiversity), the better the outcome: that is, the smaller the cascade of secondary extinctions when the initial species was removed. Unexpectedly, when pyrodiversity was low, "losing" a rare native wildflower had a stronger effect than "losing" an exotic wildflower--the loss of the rare native flower caused a larger cascade of secondary extinctions (Fig. 2). The full study was published in Ecological Applications, and you can read it here.

Fig. 2. Pyrodiversity decreases the size of secondary extinction cascades after simulated plant species losses.

We are very grateful for support of this project by Jim and Birte Falconer and by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Award FI6AC00696.